Article. By Emilye Crosby and Judy Richardson. 2015.

Key points in the history of the 1965 Voting Rights Act missing from most textbooks.

Themes: Voting Rights, African American, Civil Rights Movements, Democracy & Citizenship, Laws & Citizen Rights, Organizing, Racism & Racial Identity

By Emilye Crosby and Judy Richardson

The Voting Rights Act (VRA), signed into law on Aug. 6, 1965, was a victory for the Civil Rights Movement, southern African Americans, and American democracy. It outlawed strategies that had been used by white supremacists to disenfranchise Black citizens and included provisions to facilitate the registration of new voters. Together with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act ended most legal forms of white supremacy. Although this was important, it did not end all forms of racial discrimination, many of which were — and are — embedded in the structures of our society.

Most textbooks approach history through a top-down lens that gives President Lyndon Johnson, along with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., most of the credit for this important legislation. Both men did play a key role. But the Voting Rights Act came into being through intensive organizing and activism spearheaded by the Black community, including people often marginalized and not seen as central to our society.

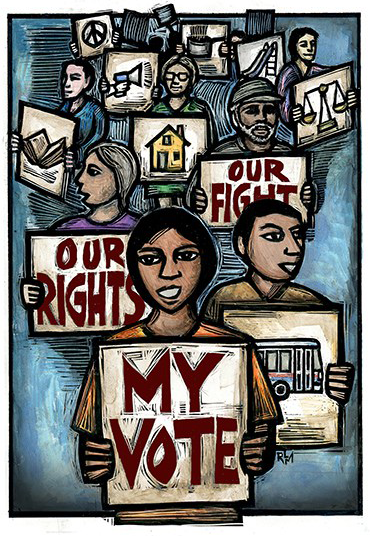

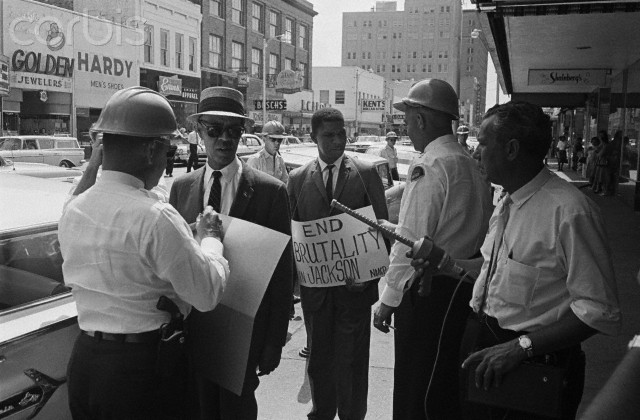

The image on the left is widely used in textbooks and popular media to illustrate the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The decades of grassroots organizing and sustained resistance, represented by the image on the right, are left out of the picture.

It is tempting to think of universal voting rights as a fundamental pillar of our country, but access to the vote has been hard fought and even today we face challenges and rollbacks. Although voting rights have always been essential, they are not a given and do not alone secure equality. The struggle for civil and human rights for all must continue. The untold history of the VRA can inform and strengthen that struggle.

Here are key points missing from most textbooks.

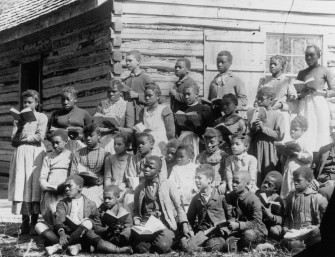

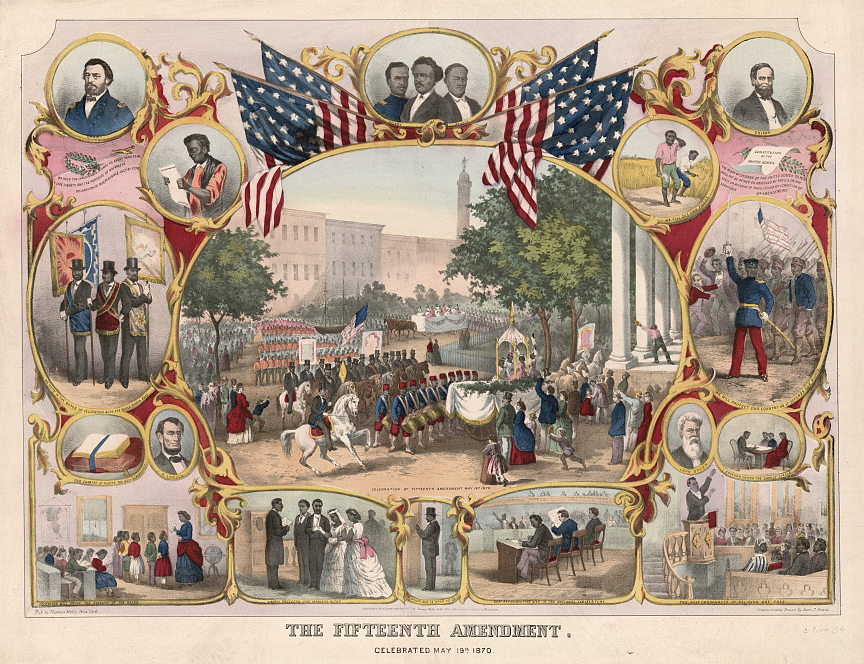

Following the Civil War, African Americans used the Reconstruction Amendments to democratize the South. Although only men were allowed to vote in formal elections, women and children participated actively in Black community meetings, even voting on delegates and platforms. Black women often accompanied men to the polls, sometimes bringing weapons for protection.

Freedpeople’s school. ca 1890. © Valentine Richmond History Center.

This community-wide engagement translated into progressive laws, including policies that laid the foundation for free universal public education. As with many rights secured by African American struggle, the Black vote expanded benefits beyond the Black community.

African American political power gained during Reconstruction was overthrown by massive fraud and domestic terrorism. The federal government stood by as white supremacists regained control over state and local governments. The timing and process varied across the South, but in the end, whites established oppressive Jim Crow laws that remained in place until the modern Civil Rights Movement.

Armed white rioters destroyed Wilmington’s Black newspaper The Daily Record.

A prime example is Wilmington, North Carolina, where whites in the Democratic Party overthrew (in a coup d’état) the legitimately elected and integrated local government, murdered Black citizens, and destroyed the Black newspaper. [Read about more massacres in U.S. history, many of the time designed to suppress the Black vote and role back gains in interracial democracy.]

Textbooks generally list the Jim Crow practices of the grandfather clause, literacy tests, and the poll tax, but less well known are the economic terrorism and violence that backed up these strategies and were the ultimate barrier to Black voting.

Mississippi sharecropper Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer describes what happened when she took the registration test in 1962:

Well, there was 18 of us who went down to the courthouse that day and all of us were arrested. Police said that the bus was painted the wrong color — said it was too yellow. . . . I went back to the plantation where [my husband] Pap and I had lived for 18 years. Mr. Marlowe, the plantation owner, had heard that I had tried to register. He said, “We’re not going to have this in Mississippi and you will have to withdraw. If you don’t withdraw you will have to leave.” So I left that same night. Ten days later they fired into Mrs. Tucker’s house where I was staying.

Later that year Hamer was viciously beaten in jail and in 1964 she testified: “All of this is on account of we want to register, to become first-class citizens.”

At times African Americans prioritized improving educational opportunities, securing land ownership, and developing the institutions — such as churches — that later provided a critical base for the Civil Rights Movement, but they never conceded their right to vote. Even when it was extremely dangerous, there were always men and women trying to register and vote.

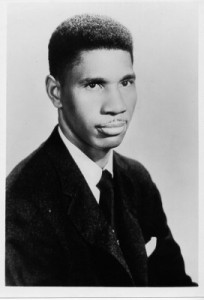

Medgar Evers (1925-1963)

In 1944, the NAACP won a landmark case, Smith v. Allwright, ruling the white primary — where only white voters could participate in political primaries — unconstitutional. This victory inspired an upsurge in Black voter registration that was reinforced by Black veterans returning home from overseas. One of these veterans was Medgar Evers, who became Mississippi’s first NAACP field secretary and was assassinated in June 1963 for his civil rights work. He describes his first attempt to vote after successfully registering:

[S]ix of us gathered at my house and we walked to the polls. I’ll never forget it. Not a Negro was on the streets, and when we got to the courthouse, the clerk said he wanted to talk with us. When we got into his office, some 15 or 20 armed white men surged in behind us, men I had grown up with, had played with. We split up and went home. Around town, Negroes said we had been whipped, beaten up, and run out of town. Well, in a way we were whipped, I guess, but I made up my mind then that it would not be like that again — at least not for me.

The Supreme Court gradually outlawed discriminatory practices, like the grandfather clause, the white primary, and the poll tax, but in general the federal government played a passive role. Even when the Kennedy Justice Department used what civil rights activist Bob Moses calls “the crawl space,” created by the 1957 Civil Rights Act to file lawsuits charging numerous Southern officials with racial discrimination in voter registration, other branches of the federal government undermined this work.

While FBI agents stood by, SNCC volunteers were beaten and arrested by sheriff’s deputies for attempting to bring water to people (many elderly) waiting in the hot sun for hours to register to vote in Selma, 1963. Image: © John Kouns.

Some white supremacist judges blocked the department’s work at every turn and the FBI only reluctantly carried out the necessary investigations. And after initially promising to protect anyone working on voter registration, the Kennedy administration backtracked and the FBI refused to protect civil rights workers, even when they were attacked on federal property in front of agents. More lives might have been lost if Black citizens had not used weapons to protect themselves and the young civil rights organizers.

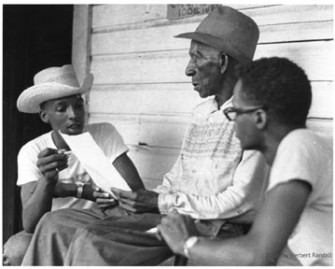

Doug Smith and Sandy Leigh participate in voter registration canvassing. Image: Herbert Randall, 1964; McCain Library, USM.

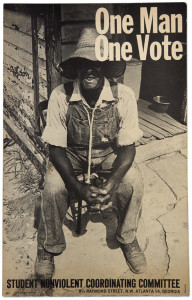

SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), an organization of young people that emerged from the 1960 sit-in movement, developed an approach to grassroots community organizing that has influenced every subsequent progressive movement. Their voter registration work in the Deep South was built around canvassing — going door-to-door, talking to people — and relied on patience, education, and building relationships. The work could be slow and tedious. It took place out of the spotlight, with few big or quick victories.

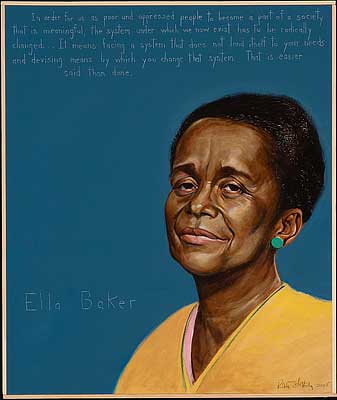

Influenced by Ella Baker and community leaders, the young people in SNCC made decisions by consensus, helped develop leadership skills in others, and challenged hierarchies that privileged wealth and education. In the summer of 1961, a group of about 16 young people put school and jobs on hold to become SNCC’s first field staff and commit to full-time movement work.

Ella Baker, center, at the Highlander Center. Photographer unknown/image from Highlander Research and Education Center.

Over the next four years — working with other organizations and allies — SNCC was successful at organizing rural African American communities and making it impossible for the country to ignore the violence and discrimination at the heart of Jim Crow and white supremacy.

Though SNCC was not acting alone, their organizing was at the heart of the movement that moved people to insist that our country eliminate the legal basis of white supremacy. SNCC’s organizing led directly to the Voting Rights Act, expanding the electorate and ending the undemocratic stranglehold of the southern Dixiecrats. Their work made the national Democratic Party more explicitly representative (in race and gender).

Perhaps most importantly, SNCC recognized and nurtured leadership in people that the rest of the country had dismissed (like Hamer). Their alliance with these everyday people breathed new life into our democracy — challenging long-standing ideas of who and what was important.

“Freedom Day” in Selma, October 1963. A long line at the courthouse to apply to register to vote. Image: © John Kouns.

White supremacists responded to the voting rights campaign by manipulating the registration process, firing and evicting people, burning and bombing homes and churches, as well as beating and even murdering people. White officials then used the low numbers of African Americans registered to vote to insist that Blacks had no interest in politics. In response, SNCC organized Freedom Days, first in Selma, Alabama, in 1963 and in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, in 1964. Whether in the punishing sun or pouring rain, people lined up to demonstrate their desire to vote. With little chance of actually registering, much less voting, they stayed in line and refused to be intimidated by white threats and harassment.

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party State Convention, Jackson, Mississippi, July 1964.

Working with a coalition of civil rights groups called COFO, SNCC also organized a Freedom Vote, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, and the Congressional Challenge. Each was designed to demonstrate that Blacks did want to vote and participate in politics. In addition, each provided an important experiential education for people who had been excluded from the political process for almost a century. Throughout this process, SNCC field secretaries were learning from the people they were working with. One result was that, in addition to helping people improve their literacy, in 1963 SNCC began to challenge the whole idea of requiring literacy to vote. They had encountered many people who had been denied education but still had more than enough wisdom to vote on their representatives.

Lowndes County, Alabama, with an approximately 80 percent African American population, but no Black registered voters, provides a wonderful case study of SNCC’s approach to using the vote. According to field secretary Gloria House,

We were helping to equip the people with the information and skills essential to running the county themselves not just as new voters but also as political leaders. We found that a review of African American and African history, giving a strong sense of historical identity, was of immeasurable significance in this process.

“Lessons from the Elections” page from a Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) pamphlet. Click to read in full.

LCFO brochure panel. Click for full view.

Historian Hasan Kwame Jeffries explains that SNCC “developed a unique political education program that used workshops, mass meetings, and primers to increase general knowledge of local government and democratize political behavior.”

This wasn’t just voting or even politics as usual. Rather, SNCC linked their “egalitarian organizing methods” with the people’s civil and human rights goals to create what Jeffries calls “freedom politics,” an approach that rejected traditional politics and instead emphasized acting on the community’s best interests. In Lowndes County, for example, Alice Moore, candidate for tax assessor, announced that she would “tax the rich to feed the poor.”

SNCC’s work followed Ella Baker’s belief that “In order for us as poor and oppressed people to become part of a society that is meaningful, the system under which we now exist has to be radically changed. . . It means facing a system that does not lend itself to your needs and devising means by which you change that system.”

When the Lowndes County Freedom Party was founded, Alabama law required that it have a symbol to help illiterate voters. They chose the Black Panther, indigenous to Lowndes, as their ballot symbol. [See the short clip below from Eyes on the Prize about the Lowndes County Freedom Party.]

This black panther is a vicious animal as you know. He never bothers anything, but when you start pushing him, he moves backwards, backwards, backwards into his corner, and then he comes out to destroy everything that’s before him.

When young Black activists in Oakland established an organization to combat police brutality, they adopted the snarling black panther symbol and the LCFP’s informal name, the “Black Panther Party.”

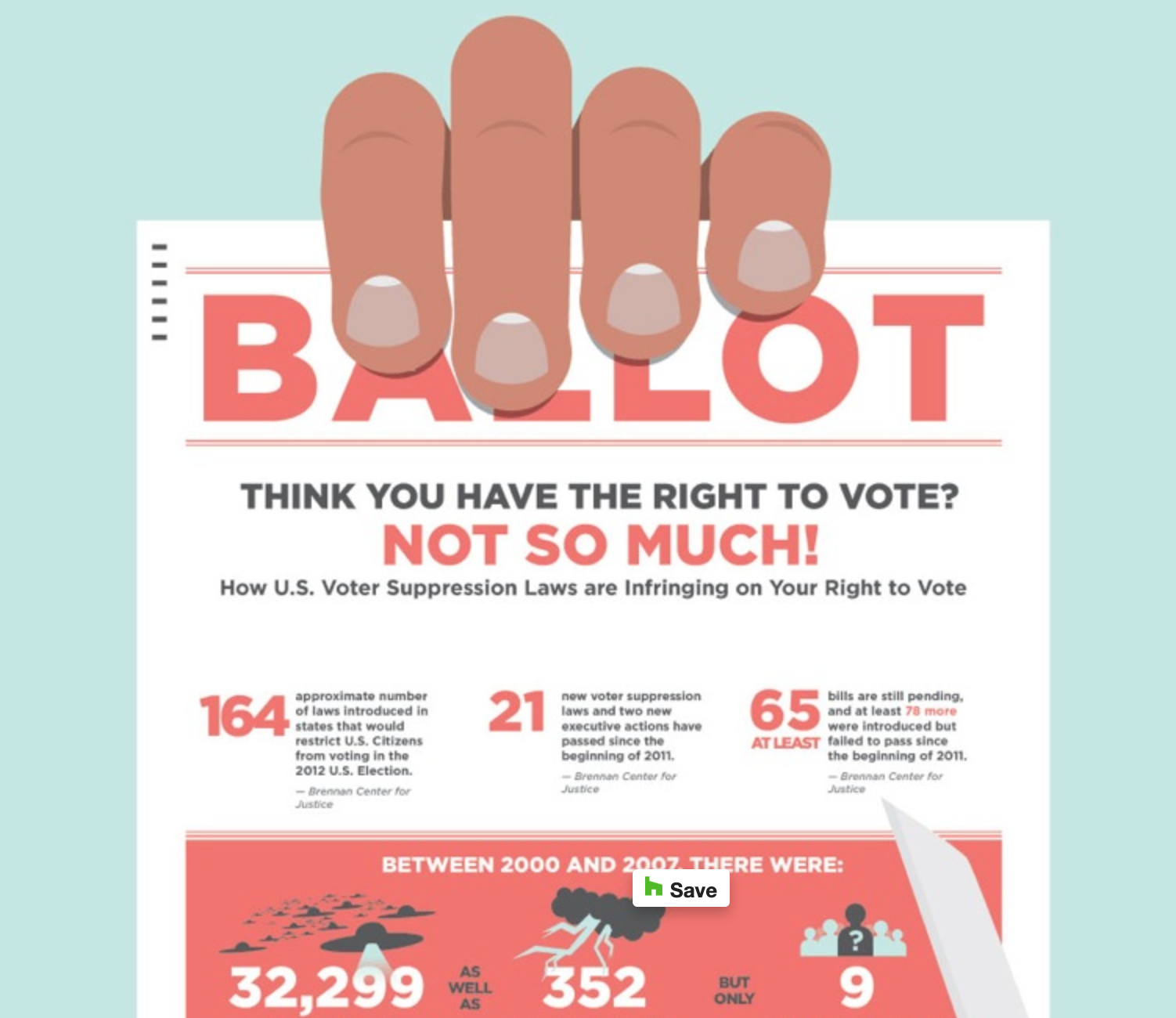

In July 2013, a deeply divided U.S. Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder. Arguing in part that it is arbitrary and no longer necessary to focus exclusively on the former Confederacy, the Court’s majority eliminated the pre-clearance requirement for nine Southern states. This means that the Justice Department can no longer check for racial bias in new laws in these states.

Given widespread efforts to block voting access in areas across the nation that were not governed by federal review, it may well be arbitrary to hold the former Confederate states to a different standard. But the response of those states, along with other forms of voter suppression enacted throughout the country, makes it clear that we still need robust, proactive tools to protect voting rights for all citizens, but particularly African Americans, students, immigrants, and other marginalized groups.

Rather than being curtailed, the Voting Rights Act should be extended. No doubt future historians will look back at today’s voter ID laws, ex-felon disenfranchisement, and other forms of voter suppression (including Jim Crow voting booths) as a 21st-century version of the literacy tests, poll tax, and grandfather clause of the last century.

The Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts removed most forms of legal discrimination against African Americans, but did not bring an immediate end to the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow.

Current protests over police brutality and the disregard for Black lives; the persistence of extreme economic and racial segregation; and the tenacity of separate and unequal schools demonstrate that although the Voting Rights Act was necessary, it is not sufficient to address white supremacy and the oppression of people of color. Unfortunately, Ella Baker’s words still echo today. In 1964 she said,

Until the killing of Black men, Black mother’s sons, becomes as important to the rest of the country as the killing of a white mother’s son, we who believe in freedom cannot rest.

Although the context has changed, there are many links between the freedom struggle of the 1950s and 1960s and today. And millennial activists are creating a new movement that builds on the work of previous generations.

Knowing some of the bottom-up history of the VRA can help students and others learn valuable lessons for today. SNCC veteran Bernice Johnson Reagon explained that the movement gave her “the power to challenge any line that limits me. . . . And that is what it meant to me, [it] just really gave me a real chance to fight and to struggle and not respect boundaries that put me down.”

| Emilye Crosby is professor of history and coordinator of Black Studies at SUNY Geneseo. She is the author of A Little Taste of Freedom: The Black Freedom Struggle in Claiborne County, Mississippi and editor of Civil Rights History from the Ground Up. She is working on a book length project, Anything I Was Big Enough To Do: Women and Gender in SNCC, with a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Read more. | |

| Judy Richardson was on the staff of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) from 1963-66 and was researcher, series associate producer, and education director for the 14 hour PBS series Eyes on the Prize. Her other films include Malcolm X: Make It Plain and Scarred Justice: The Orangeburg Massacre 1968. She is currently on the SNCC Legacy Project Board and the editorial board for the SNCC Digital Gateway collaboration between the SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University. She co-edited Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC. Read more. |

The authors thank the Teaching for Change staff who collaborated on the development of the list of points and Deborah Menkart for her editing. Thanks also to Bill Bigelow and Kathleen Connelly. This article draws from “The Selma Voting Rights Struggle: 15 Key Points from Bottom-Up History and Why It Matters Today” by Emilye Crosby (January, 2015). There is a longer version of this article called “Voting Rights Act: Beyond the Headlines.”

| Justin Behrend. Reconstructing Democracy: Grassroots Black Politics in the Deep South After the Civil War (University of Georgia Press, 2015). | |

| Elsa Barkley Brown. “Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere: African American Political Life in the Transition from Slavery to Freedom.” Public culture 7 (1994), 107-46. | |

| Bernice Johnson Reagon. “The Borning Struggle: An Interview with Bernice Johnson Reagon” by Dick Cluster in Radical America. (Note: “Borning Struggle” is the first article in the attached journal. Photo: Ella Baker at the Highlander Center.) | |

| SNCC Digital Gateway. June 1966 Meredith March Against Fear. Description of the March Against Fear, led by James Meredith in June of 1966 to encourage African Americans to vote one year after the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Meredith was shot and other civil rights leaders and activists stepped in to carry on the March, registering voters along the way. |

Teaching Activity. By Ursula Wolfe-Rocca.

Unit with three lessons on voting rights, including the history of the struggle against voter suppression in the United States.

Lesson. By Bill Bigelow. 17 pages.

This role play engages students in thinking about what freedpeople needed in order to achieve — and sustain — real freedom following the Civil War. It’s followed by a chapter from the book Freedom’s Unfinished Revolution.

By Ursula Wolfe-Rocca

From voter ID laws to voter-roll purges, gerrymandering to poll closures to the deadly in-person voting conditions during a pandemic, the right to vote is under attack and the stakes are high. It is critical that students learn about the fight for voting rights, past and present.

Book — Non-fiction. By Kidada E. Williams. 2023. 352 pages.

An account of the brutal white supremacist violence and terror that formerly enslaved people were faced with during Reconstruction.

Book — Non-fiction. By Lawrence Goldstone. 2020. 288 pages.

This young adult book documents the long and ongoing struggle for voting rights for African Americans.

Profile.

Brief biography of Ella Josephine Baker, 1903–1986, activist and civil rights organizer.

Profile. By Dernoral Davis.

Medgar Evers (July 2, 1925—June 12, 1963), Civil Rights Movement activist in Mississippi.

Book — Non-fiction. By Martha S. Jones. 2021. 368 pages.

This book excavates the lives and work of Black women from the earliest days of the republic to the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act and beyond.

Book — Non-fiction. Edited by Faith S. Holsaert, Martha Prescod Norman Noonan, Judy Richardson, Betty Garman Robinson, Jean Smith Young, and Dorothy M. Zellner. 2010. 616 pages.

An unprecedented women’s history of the Civil Rights Movement, from sit-ins to Black Power.

Teaching materials and guides on the 15th Amendment’s significance in 2020 — its 150th anniversary and an election year.

Patrick S. O'Donnell on August 6th, 2016 - 10:02am The iconic black panther symbol was borrowed was borrowed from a WPA (Federal Arts Project in particular) poster (1936) for the Brookfield Zoo in Chicago (also known as the Chicago Zoological Park). You can see the original here: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/96524657/

France in California on August 20th, 2015 - 3:07pm When I took the Quiz I was ashamed that I did so poorly! America needs educating about the history of Voting Rights and many other thorny subjects!

CMA on August 7th, 2015 - 7:03am This is an excellent resource for educators and everyone else, and it rightly emphasizes the importance of grassroots struggle in forcing our political leadership to broaden access to the ballot box. The federal government has always been a reluctant ally, a fickle friend that responds only when pressured. As a history teacher, I have one bone to pick about the casual dismissal of “textbooks.” Although there are some egregious examples of poor textbooks (such as the elementary school textbook in Virginia that claimed slaves were happy), by and large the textbooks that are written by scholars today do indeed address these issues. They are much, much better than the textbooks of the 1970s and 1980s. This in itself is a victory to be celebrated — it’s taken a generation or two of solid scholarship to shift how the historical profession writes about black history. The problem I encounter in students is that certain ideas (e.g. the top-down approach to understanding history) seem to be embedded so deeply in our culture that even a thoughtful, penetrating history textbook, book, or course has trouble dislodging it. That is why this ongoing work is so important.

lizzy on August 4th, 2015 - 11:56pm i wish every American would be required to take a class that taught this history, it might help with the racial issues we are having in America today. Never have African Americans been given their legitimate freedom to vote, own a home, attend school, get a good job, and yet many Americans believe there is no reason for many African Americans to be struggling and angry today. Racism is using your power to hold another race of human in an inferior position and deprive them of their needs. It has become very evident that with the election of an African Americans, the fear of African Americans making progress has propelled the “racist” American to do everything possible to stop that progress. History teaches us that human beings have struggled with these issues throughout the world.

Comments are closed.

© 2024 Zinn Education Project

A collaboration between Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change

PO Box 73038 Washington, D.C. 20056

Email: zep@zinnedproject.org

Design elements by Lauren Cooper.